CHOOSING WHO CAN BE USING THE "NIGGER" WORD

CHOOSING WHO CAN BE USING THE "NIGGER" WORD

I waited a bit to comment on comedian Michael Richards’

comedy club “nigger” meltdown, in part because there were other more pressing things

to write about, in part because the use of the word “nigger” in American life is

a serious, long-term discussion that need not rise to the surface only when it has

become the talk-show, blogsphere fad of the moment. I’ve written on the subject before,

at length, and expect to do it again, from time to time.

For those who missed it–if that is possible–former “Seinfeld” television star Richards

made national news late last month when he was caught on camera during a routine

at LA’s Laugh Factory responding to black hecklers in the audience by repeatedly

calling them “niggers.”

"Throw his ass out,” Mr. Richards shouted. “He's a nigger!

He's a nigger! He's a nigger! A nigger, look, there's a nigger!" And when several

in the audience voiced their disapproval of his tirade, he said, "They're going

to arrest me for calling a black man a nigger." Richards also told the men,

“Fifty years ago we'd have you upside down with a fucking fork up your ass.”

"Throw his ass out,” Mr. Richards shouted. “He's a nigger!

He's a nigger! He's a nigger! A nigger, look, there's a nigger!" And when several

in the audience voiced their disapproval of his tirade, he said, "They're going

to arrest me for calling a black man a nigger." Richards also told the men,

“Fifty years ago we'd have you upside down with a fucking fork up your ass.”

For those who know something about recent American history, the reference to American

lynching immediately took Mr. Richards’ remarks out of the area of mere name-calling

and into the realm of the indefensible, and there were more than enough condemnations

from sources various and sundry to fill several file cabinets.

But Mr. Richards also had his defenders, people who wondered why it is okay for African-Americans

to use the word “nigger” while others are condemned for it.

Typical of that sentiment was someone signing himself “Jack” at Matt Dentler’s entertainment-based

blog (http://blogs.indiewire.com/mattdentler/), who remarked that it is “two-faced

of civil rights leaders to make a mountain out of mole hill with the comedian/actor

Michael Richards’s affair where he used the word ‘nigger’ multiple times. Black comedians

on the Black Entertainment Channel can scream ‘nigger’ and the audience will scream

with laughter with some almost falling out of their chairs. Pardon my French, but

if a Nigger says ‘nigger’ he is not engaged in a racist tirade and he can get paid

top dollar for doing it.”

“Sillier yet,” Jack continued, “the word "nigger" is so taboo that some

people are expected to make reference to it by saying ‘the n-word’. We do not have

a ‘g-word’ for ‘gringo’ [etc., etc. etc.] …

Jack concluded that Mr. Richards “was mouthing off at a night club where folks expected

some insults. Black folks, especially the civil rights leaders, ought to be able

to roll with the punches like everyone else.”

Like everyone else? No, let’s leave that. It’s a distraction.

In order to emphasize that we are advancing a universal truth rather than a point

of personal privilege, let us make our assertions, first, in broader terms rather

than the particular: those who are or have been the victims of some form or other

of social oppression–racial, religious, gender, et. al–forever retain the right to

use, in whatever way they want, the epithets used against them in advancing that

oppression. Those who were not and are not the victims, do not (except under special

circumstances, which we will talk about in a moment). That seems simple enough.

In other words, Korean-American comedian Margaret Cho can make all the jokes in Asian

dialect because she is of Asian descent, but comedian Rosie O’Donnell cannot. Ms.

O’Donnell, on the other hand, is free to joke at will about lesbians, while for Ms.

Cho (unless she is lesbian; I don’t know her well enough to determine), that is forbidden

territory. So it is, also, with my Native American brethren, who can ridicule Uncle

Tonto all they want. I would do so at my own risk.

There are, of course, exceptions to this rule.

The first is the “walk a mile in my moccasins” exception–those who are willing to

accept the burdens of the oppressed are also made benefit to whatever perks may accrue

(Johnny Otis, the Berkeley native musician who gave up his Greek ancestry early in

life to identify himself exclusively as African-American, heart and soul, comes instantly

to mind, here). The second exception are those who use ethnic epithets in their humor,

for example, as methods of healing rather than hurting. The comedian Richard Pryor

had the knack of it, almost always beginning his routines by ragging on himself–by

the time he moved on to black people in general (who he almost always referred to

as “niggers”) and then, finally, to other groups, the effect was more often than

not to show the universal humanity in all of us, rather than an emphasis on the differences.

But few of our non-African-American compatriots who seem so eager to be unleashed

to use the word “nigger” at will appear willing to put the time or the energy in

to qualify for either exception. Instead, like little children impatiently eyeing

the bright packages under the Christmas tree, the ask from time to time “can’t we

say it yet?,” sighing when told “no,” as if the word “nigger” were a present

that they just cannot wait to open.

The word “nigger” itself has vastly different effect upon most African-Americans,

depending upon who is using it.

For many years of our time here in this country, it was one of the terms we most

often used to apply to ourselves. When the term went out of general use as a self-identification–supplanted

by a succession of terms from “colored” to “negro” to “Negro” (with a capital “N”)

to Black (with a capital “B”) and then to the present-day “African-American”–“nigger”

was taken over exclusively as a perjorative and a put-down by anti-black racists.

But even in the 1950’s and the 1960’s, a move was afoot among African-Americans to

try to recapture the word, cleanse it, and rob it of its sting.

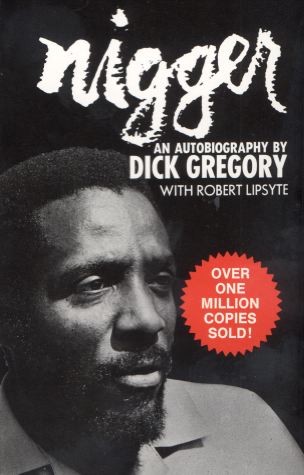

In 1964, the comedian Dick Gregory titled his autobiography “nigger.”

On the dedication page is a note to his mother by way of explanation: “Dear Momma,”

it reads, “wherever you are, if ever you hear the word ‘nigger’ again, remember they

are advertising my book.”

In 1964, the comedian Dick Gregory titled his autobiography “nigger.”

On the dedication page is a note to his mother by way of explanation: “Dear Momma,”

it reads, “wherever you are, if ever you hear the word ‘nigger’ again, remember they

are advertising my book.”

That was, in part, the intent of many of the black comedians of the 60’s and 70’s–Richard

Pryor most famously and notably–attempting to defang the term by continued use. In

doing so, they were mirroring the use of the term in “non-polite” black circles.

One of the unspoken truths about black life is that many black people have never

stopped referring to each other by that term–not in a way of putting each other down,

but in descriptions that can range from admiration to friendship to affection, and

even love. This is a fact not widely-known outside the African-American community

but, then, why should it be?

Thus, the adoption of the term by today’s hip-hop generation–transformed from straight

“nigger” to its variation “nigga”–is not a new innovation at all, but merely a continuation

of a long-term trend. What is different is that through cd’s and videos, the rest

of the country–indeed, the world–is now privy to what used to be an exclusive and

private dialogue.

And, in fact, that usage of the term by African-Americans is by no means universally

accepted among African-Americans, and there is a fierce and healthy dialogue going

on amongst us as to its appropriateness under any circumstances. The results of that

discussion have yet to be determined.

Meanwhile, though the marvel of modern communications has allowed our non-black friends

and not-so-friends to listen in to its use by African-Americans, this should not

be construed as an invitation to join the “nigger” chorus. The term “nigger,” when

used by anyone but an African-American, almost regardless of the context, revives

dark and difficult memories–the rape of Africa, the slave trade, the horrors of the

Middle Passage, the yeas of Southern chain slavery, the Hundred Years of Terror between

the end of Reconstruction and the beginning of the Civil Rights Era. We live, now,

in the backwash of that foul history. And though African-Americans of my generation

are mostly polite and mention it far less than we think about it, the consciousness

and memory of our history, here, remains heavy on our minds. For almost all of us

of my generation it will never go away, not to the end of our lives.

A day will come when the word “nigger” will have lost its edge and bite, and generations

can read of it and talk, dispassionately, of its history and its meaning. But that

is not this day. And until that time, the word “nigger” belongs to African-Americans,

and we alone have the right to regulate its use.

We would ‘preciate it, a good number of us, if others would honor that.