THE UNION(S) OF THE ALLENS AND THE REIDS

Married Couples Maybelle Reid Allen and Ernest Allen (top) And Betty (Allen) Charbonnet Reid And Mel Reid (bottom)

A HISTORY OF REID'S RECORDS

[NOTE: The Reid's Records Story is included in both branches of our family website—Allens and Reids—because the Record Shop represents one of the several comings-together of those two pioneer Bay Area African-American families. Reid's Records was founded by Mel Reid and was later owned and managed by his former wife, Betty Reid Soskin, an Allen descendant. The record shop is now owned and managed by David Allen Reid, Mel Reid and Betty Reid's Soskin's son, who is descended from both sides of the family.]

INTRODUCTION

By Betty Reid Soskin

The Story of Reid’s is the story of many of the small black businesses that came into being through the ambition and hard work of young people all over the country at a time when independence was the essential ingredient in the making of a life.

The young Reid family experienced all of the tears and triumphs that have colored the lives of other ordinary black folks, with the essential difference that the lows may have been the equivalent of those suffered by many others for reasons beyond their control—while the highs tended to soar like the mighty eagle! We experienced the full range of human experience, and survived.

This is the story of one small African American enterprise that struggled to mixed reviews in the American marketplace for over half a century. This piece first appeared in December of 1989 in the East Bay Express as a lead article written by staff columnist, Lee Hildebran. Ran across it in my files while searching for relevant material for this website. I read through it after many years that have been dramatically lifechanging and found it still factual and powerfully “real.” I would not change a word, nor do I regret having lived every minute of it. This was a picture of Reid’s at year 44 of survival of what has now been 62 years of coping in a changing world. So much has happened over time.

The second generation of ownership is now fully in effect. The information age is in full bloom. Mel died shortly after this story was written and our oldest son Rick who grew up behind the counter from the age of 3 months, has now passed on, in 1995. Our youngest son, David Allen Reid, is the proud proprietor.

David Allen Reid

Current Owner and Operator of Reid's Records

SELL A JOYFUL NOISE

East Bay Express

December 1, 1989

By Lee Hildebran

One afternoon in 1973, I ran into Mel Reid on the sidewalk outside the MacArthur-Broadway Shopping Center. He and a small group of other middle-aged black men, all proprietors of local mom-and-pop record stores, were carrying picket signs protesting the opening of a new record store. The handsome, normally mild-mannered Reid was boiling! His sign urged a boycott of the new store, claiming that its existence was unfair to the black community.

Mel, who’d operated Reid’s Records on Sacramento Street in Southwest Berkeley since 1945, told me that this store, part of a new chain, was a direct threat to his business and those of the other picketers. The new store was owned by a local record distributor from whom all of them had been buying much of their stock. Because they specialized in soul, gospel, and blues, these black record merchants had been able to hang tough in the face of competition from such chains as Discount Records and Tower, which had long since driven most white mom-and-pops out of the vinyl game. But this new store was different--and, in their view, much more dangerous. Because the distributor primarily serviced small black shops, it knew which records were hot in the black community. Now the company’s wholesale arm would be able to deliver product to its retail branch without much markup, and could easily undercut the price of the small merchants.

Betty and Mel Reid

Five years later, Betty Reid Soskin, who'd founded Reid’s Records with Mel, found her former husband in the back of the store in a coma. (He died in 1988, after a long battle with diabetes). The business Betty walked into was a shambles. In a desperate attempt to generate profits, Reid’s Records had started carrying water pipes and other drug paraphernalia; black light posters of naked couples in various sexual positions glowed from the walls. The duplex next door, which Betty and Mel had purchased at the time of their marriage in 1942 had been seized by the IRS. The store itself was in foreclosure. Betty, who had divorced Mel in 1971 and married a UC Berkeley research psychologist, resolved to step in, stabilize the business, make peace with the feds, then sell it so that her four children, two of whom worked there, could salvage something from it. Mel had systematically wrecked what would have legitimately been theirs at some point,” she explained. “It was our estate. It was all we had. The house was gone. This was it.” “What I found was a paradox; on the one hand a total failure and on the other, a neighborhood institution that had developed a life of its own.” She quickly learned to respect that as something to build on.

The shop was in disarray and the street outside was being torn up to remove the Santa Fe railroad tracks. The concrete street and sidewalks had disappeared. The neighborhood itself had deteriorated badly; there was a heroin shooting gallery directly across the street. Betty, who hadn’t been directly involved in the business since the late ‘40s, quit her job as an administrative assistant at UC Berkeley and set about restoring order. First she threw out the “head shop stuff” and the dirty posters and replaced them with items that would appeal to the eighty percent of the store’s clientele that came to buy gospel records. “I filled the window with Bibles and changed the inventory around to things that people didn’t want to steal,” she said. Knowing little about the business at the time, she took to allowing the customers to create the inventory. “If 3 people asked for something I ordered 5 for that week. Over time the customers shaped the business in their own image.

Today, eleven years later, Betty Reid Soskin is still running Reid’s Records. It remains a leading outlet for gospel records, as well as for gospel sheet music, concert tickets, choir robes, and other church-related items. In business continuously for the past 44 years, it is one of the oldest records stores in the United States and certainly the oldest in the Bay Area.

“It’s still not making a ton of money and probably never will,” she told me recently, “but I discovered along the way that that’s not what it’s all about.”

Betty Charbonnet was born in New Orleans in 1921. Her father and grandfather were architects and builders who built Catholic Churches and convents. She moved with her family to East Oakland in 1927.

“Were they middle-class? I asked.

“That’s a white question,” she responded. “The reason it’s a white question is that, at least at the time that Mel and I were growing up, that was not the way the black community was divided. Lower, middle, upper class meant almost nothing. There were too few of us at the time to have made those kind of social divisions. It might have been done on skin color--there was a lot of that--but not in terms of economic levels.

A Gathering Of Allens And Relatives In East Oakland, 1930's

“It was an interesting time in which to grow up. There weren’t enough blacks here to have rules made against us. We could all go into one living room for a party and often did. We were together by choice (or so we believed). It had little to do with anyone not wanting us. That doesn’t mean that there wasn’t racism. It existed. In fact, it was ugly, but we didn’t experience much of it. There were about 15 (black) families east of Lake Merritt. We all knew each other, and socialized together.

“We faced those problems when the war came about and suddenly there were enough of us to be set apart. And then it really got ugly.”

Betty, an attractive Creole teenager attending Castlemont High School, met Mel Reid, a good-looking cafe au lait Berkeley youth from a pioneering black California family, at San Pablo Park in West Berkeley. “I went to a baseball game every Sunday when I was thirteen, fourteen years old,” she remembered. “I was sitting in the stands with my grandfather, Papa George, when Mel came by on his bicycle. He was on his paper route. I used to come from East Oakland with Papa who came out to watch the black teams, the barnstormers, play at San Pablo Park. That was before Mel was a California Eagle. Lionel Wilson was the pitcher at the time that Mel played on the team.” Mel Reid’s family came to California during the Civil War to mine near Sacramento. His ancestors figured prominently in the settling of San Francisco and later the East Bay. The family eventually moved from Angels Camp, San Francisco, and then to Berkeley where Mel was born in 1917. His father worked all his life at the bakery that made Wonder Bread.

“He never got off the loading dock,” Betty said of Mel’s father, Tom Reid. “He loaded one-hundred pound sacks of flour from rail cars for fifty years. The black man never got off that dock here in Berkeley, until he retired at 65.

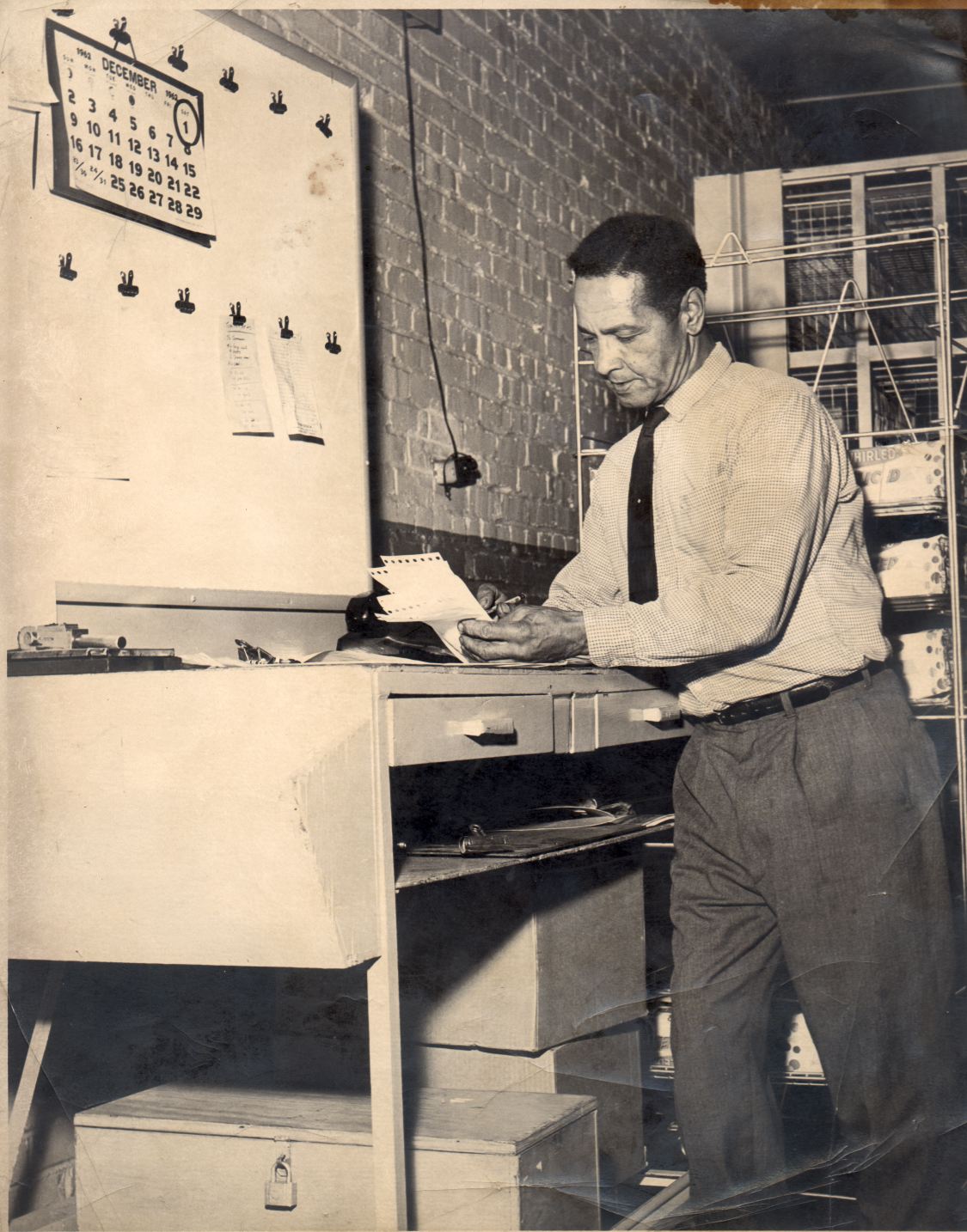

Tom Reid At Work On The Wonderbread Loading Dock

“When Mel graduated from Berkeley High School, his ambition was to be a bakery wagon driver for the company where his father had worked all those years. But they wouldn’t hire black drivers, nor would he be allowed to join the Teamsters union, a prerequisite. That’s the reason that he went into business for himself.”

During World War II, Mel worked at the shipyards in Richmond at night and as a playground director at San Pablo Park during the day. He and Betty were married in 1942 and bought the duplex on Sacramento Street. Southwest Berkeley was still an integrated neighborhood, but it had long been the hub of black business and social activity in the East Bay.

“Mel met a man, a wonderfully kind man, Aldo Musso,” Betty recalled. “He had built this duplex next door for his bride when they were married. Mr. Musso had a jukebox route, and he brought Mel in to show him the business ‘cause Mel wanted to go into business for himself when the war ended. He was going to have a black jukebox route. I don’t know where he met Mr. Musso, but Musso saw us as a young couple of kids, just married and was interested in us. He made it possible for us to buy that house next door for $745 down payment on a $4200 mortgage -- and took Mel into his business.

“Mel saw that there was no way to get black records--they were called ‘race records’—and the black population had absolutely during the war. A new market. While Mel continued working his other jobs, Betty operated the store, selling 78s out of the garage door window. The discs were kept in orange crates, the money in a cigar box. There was a playpen in the corner for their infant son, Rick. Business was slow at first. But one record quickly changed that. The record was a blues by Wynonie Harris, a two-part song called “Around the Clock.”

“Well, I looked at the clock; the clock struck one. She said, ‘Come on, Daddy, let’s have a little fun,’” Harris wailed over an all-star Los Angeles bebop combo led by drummer Johnny Otis. The double-entendre lyrics, based on the time-honored blues theme of making love all night and all day, moved ahead: “Well, the clock struck seven; she said, ‘Please don’t stop. It’s like Maxwell House Coffee, good to the last drop...’” “Around the Clock” was one of the biggest hits in the black community in 1945.

There were only two other record stores in the Bay Area selling popular black records at the time -- Wolf’s in West Oakland and Melrose on Fillmore Street--and neither advertised. Realizing the potential of “ Around the Clock,” the Reid’s bought time on KRE, which was just beginning to mix jazz into its middle-of-the-road format, to plug the record and their little store.

“That very day,,” Betty recalled, “people were lining up in front of the place to buy that record. We sold ‘em by the box. That launched the shop.”

Wynonie Harris Record "Stormy Night Blues" Released Following "Around The Clock"

Reid’s initial success came from selling records of a type of music that would soon be dubbed “rhythm and blues.” They sold no gospel records in the early days. By the late ‘40s, the couple had made enough money to build a home in Walnut Creek. Betty dropped out of the business in order to stay at home with the kids who now numbered two with a third on the way.

Bob Chatton sold records to Reid’s from 1947, when he opened his record distributorship in Oakland, until 1970, when he sold out to United Artists. “I started very small and needless to say, I couldn’t get any good labels like Columbia or RCA,” he recalled. “I could only get race records, as they called them in those days. But, ironically, those are the ones that broke loose. I really went to town because I had over one hundred labels. Mel Reid was one of my very best customers. He was a very, very good businessman, an honest, hardworking fellow. He paid his bills on time.”

After Betty retired from the day-to-day activities of the business, Mel’s uncle, Paul Reid, became involved. With his “Gospel Gems” radio program on for 3 hours on Sunday mornings, KWBR (now KDIA), Paul was the Bay Area’s leading gospel disc jockey. This gave Reid’s an inside track on the gospel record market. Paul also promoted gospel concerts, regularly packing the huge Oakland Auditorium Arena with shows that featured such stars as the Five Blind Boys of Mississippi, Rev. James Cleveland, the Staple Singers, Shirley Caesar, Rev. C.L. Franklin, the Caravans, and Reid’s became the outlet for gospel tickers.

Paul Reid (right) Emceeing A Gospel Concert

Mel Reid And Aretha Franklin

“Mel was Mr. Big in the gospel world,” Chatton told me. “We had a lot of gospel stuff, like Chess and Checker, and Reid’s was the biggest (outlet) of all the stores. He and his uncle did a fantastic business. They sold more spiritual records than anyone in the state.”

After Paul Reid’s death in the late ‘60s, Reid’s Records began to fall apart. Chatton recalls a visit from IRS agents asking questions about Mel. Apparently, Mel had gotten his hands on some blank Chatton invoices, forged them to indicate purchases he’d never made, and filed them with his tax return. Besides Mel’s own mismanagement, the store was plagued by increasingly frequent burglaries (one every 3 months for a time. Mel took to sleeping in the office in the back of the store, a rifle by his side. He was no longer going home to his family. His marriage and his life began to disintegrate. The streets had beaten him, finally, as the community continued its steady decline into degradation and despair.

The store began to mirror the streets of inner cities everywhere.

Iron bars now cover every window of Reid’s Enterprises, a two-story stucco-and-concrete complex built in 1964 during the good times -- next door to the duplex that was the store’s original location. Betty sells records and religious paraphernalia on the first floor and is currently renting the second story to Inner-City Services, a city-funded program that trains young people in computer programming and repair and helps them to find jobs. The city has made ongoing, albeit painfully slow, attempts at redevelopment, but the neighborhood hasn’t improved much since Betty took over the business eleven years ago; rock cocaine has simply supplanted heroin as the drug of choice.

“What’s the difference between crack cocaine and heroin?” she pondered between customers, one who’d come to be fitted for a choir robe, another looking for instrumental gospel music. “I haven’t the vaguest notion. They’re all the same to me. They seem to create the same problems. “I’m very unsophisticated about most of it. I see the effects of it. There are children in this community whose parents I’m sure are involved.

“Drugs don’t seem to be the biggest problem. Hopelessness is the biggest problem. It’s not crack and it’s not heroin. They’re simply symptomatic. Nobody looks at that. What I’m a looking at is a hell of a lot of hopelessness. I’m looking at second and third generation joblessness. I’m looking out at men who have never had a job and guys who can’t go home because the social worker might show up and the wife and kids are on welfare ... . The streets are filled with men like that.

“That was my passion about getting the street redeveloped, but every time we yelled, they brought in more police. That wasn’t what it was about.” The problem is about public health and economics -- poverty breeds despair and despair breeds crime. Long active in lobbying for humane redevelopment, Betty has a clear vision of the neighborhood she’d like to see. “We don’t want the people who are presently here to be displaced. The people who are still on the block will be subsidized so that they can afford to remain. The rest of the housing will be limited-equity co-ops. Some will be market-rate, some will be subsidized, and some must be very low cost.

“One of the things I’ve learned from being down here is that as long as the common denominator is poverty, things won’t change very much. My dream is that this remain a black community, because black kids need to see the full spectrum of black life. Normally when blacks make it--the only reason I’m back here is that I choose to be, but I was outside--we move and leave behind the people whose children never see anyone who’s successful. As long as we ghettoize people that way, there’s nowhere kids can see the full spectrum of black life.

“I’m not suggesting just black people. I guess what I mean is that a David Sanborn or a Kenny G. can play in my band anytime. They’re derivatives of black culture --- but the common denominator is black music. Johnny Otis could live next door, because we are both pushing black culture. That’s what I’m talking about. This area ought to be integrated, but black-oriented. That’s what I’d like to see.

Although gospel records and related items comprise the vast majority of the store’s inventory, Betty stocks many popular soul, funk, and blues records in order to service folks in the community who can’t or wont make the trip to Leopold, Tower, or Rasputin’s. But she’s fussy about what she’ll carry. She has, for instance, Clarence Carter’s double entendre “Strokin’,” but draws the line at Marvin Sease’s “Candy Licker,” which she describes as “single-entendre.”

Three years ago, Reid’s made the news when a Tribune reporter spotted a sign in the window explaining that the store was refusing to carry “ Bigger and Deffer, rap star LL Cool J’s hugely popular debut album. Local television and radio stations picked up the story, and Betty subsequently adopted a policy of not stocking most rap releases. “It was talking about his Uzi and blowing somebody away,” she said of the LL Cool J record. “Kids don’t need to hear that kind of stuff. When I really began to pay attention to raps, other things began to surface. I began to look at record covers with kids standing around with guns, with tons of gold chains around their necks and the values that that suggests.

“When a adult walks in here and asks for ‘Strokin’ or any of the other colorful blues, I don’t feel like I have to change them or their tastes. The difference is that the children who were coming here, from 7 years-old up, were buying these cassettes, putting them into their Walkmans, listening through earphones, and nobody but me was in a position to know what they were hearing. I don’t think most of their parents knew what that stuff was. That was proven out, because when I banned it, parents would come in with their kids and the kids would want to buy one of those raps. I’d ask the parent, ‘have you heard this?’ The parent invariably had no clue.

“What was happening was that the industry was directly piping things into the ears of these kids in ways that didn’t make sense. That is not related to people’s rights to hear “blue” blues records. That’s their business. I don’t go out of my way to carry them, but I don’t censor people. I don’t even censor kids--I tell ’em to go to Leopolds. I’m not dealing with their right or lack of right to do something. Let’s face it--I already decide what my clientele is gonna buy when I buy what I buy to sell from my shelves."

Betty Reid Soskin (left) Presenting A Community Award At Reid's Records

Most of the records and cassettes Betty buys to sell to her customers are gospel. Her prices are higher than the big stores downtown--usually the full $8.98 list price--but she keeps up with new releases and catalog favorites better than the larger stores do and maintains a faithful clientele.

One of the reasons for specializing is that there’s no way we can compete with the discount houses--Rainbow, Tower, you name it,” she explained. “Those are the people who can buy direct (from the major labels),. I specialize and deal with a lot of small labels. I’ve got to garner my things in dribbles and drops. I don’t buy in volume. I’ve got to take the full markup.”

Even though she can’t buy directly from the majors--like other mom-and-pops, Reid’s gets most of its stock from sub-distributorships--label executives call Betty from time to time. ”They’re looking for talent or that sort of thing,” she explained. “I’m trading on the reputation that Mel built up over the good years, but I still buy at a full markup. I don’t get any breaks. As a matter of fact, my records are loss-leaders for the other things that I carry. That was a calculated decision. The records bring people here and I have to keep my stock high and I have to stay on top of new releases. But they don’t pay the overhead. What happens is that people come in; they buy Bibles; they order choir robes.”

Choir robes have become a lucrative item for Reid’s. They really carry the business,” Betty said. “I do several choirs a months. Those choirs have anywhere from 20 to 150 members. It’s a very easy business. I measure people one at a time while they practice their music.

Reid’s does a national mail-order business and publishes a handsome annual catalog, currently 138 pages thick, of its non-music religious merchandise. There are children’s books with such titles as Jesus, My Friend, and God’s ABC Zoo, Biblical puzzles and puppets, Christian greetings cards, communion chalices and linens, baptismal bowls, crosses of every size, church administration forms and records books, Bible story audio and video cassettes, and candles. Many of the items are on display at the store.

Although Betty Reid Soskin says she’s “not a particularly religious person,” she has developed a profound passion for modern black gospel music. In her monthly newsletter (circ. 20,0000) and in all of her advertising , she uses the slogan, “Contemporary Gospel is Jazz Come Home,” She views gospel as the cutting-edge music of our time and as a viable alternative to rap and other forms of popular music currently in vogue among black youth.

“I really wonder where the Wynton and Branford Marsalises of the future are going to come from, because the culture is rewarding a level of art that I question,” she said. “To the extent that that’s true, I think it’s doing the kids a disservice. Lots of youth used to come through the public school system knowing music, learning instruments. But given the (budget) cutbacks, those programs are fast disappearing or have disappeared totally.

“I’ve got some feelings about what that’s doing to us as a people. I worry about the fact that when I look at these award shows, you’ve got Jazz Jeff, whatever, all these guys--’bump-ditty-bump.’ I mean, come on, we are worth so much more than that. If you listen real closely to ap, you’ll find some relevant poetry and I don’t quarrel with that, but it’s to the sacrifice of our musical heritage. That worries me.

“That’s part of my excitement with gospel music. The good jazz singers are in the churches doing black gospel. And the good musicians are in the churches. That’s where the edge is. It’s less and less in the public. It’s coming form the choir lofts. There was a time when the movement was from the choir loft to the clubs. That was the route taken by Sam Cooke, Johnnie Taylor, Aretha Franklin et al. But for some reason, that path has been interrupted. Now, you’ve got kids who are either bridging both or staying within the churches and doing their thing within the context of religion. It’s some of the most exciting music I’ve ever heard. I’m not here because it’s a business. I’m here because I love black gospel music. I think it just brilliant!

“You have to understand, I’ve lived as a black merchant’s wife, as a suburban wife with a swimming pool in the backyard, and as an academic spouse. I’ve bridged a lot of lifestyles, but one of the things that I’ve learned is that one of the basic differences in black and white cultures is that in white culture what gets rewarded by how well you do the thing that precedes you. Ballet was based on Pavlov and what she set down. The symphony--it’s how close you get to perfection of the notes already created and shaped. It’s how well you match what has gone before.

“In the black world, it’s altogether different. What gets rewarded is the creativity and individuality stamped. If you do it like somebody else did it, you aren’t anywhere. That’s what it’s all about. What it’s about is interpreting from here.” Betty points to her heart. “I think that’s why black culture gets emulated all the time--because it’s always creating --making new edges --- new pathways in ...that’s what’s exciting to me.

“That’s not true of pop. When I listen to pop or when I watch Soul Beat or one of those programs, all those kids sound alike to me. All the beats are the same. They all say ’baby’ or they all say ‘girl.’ All the guys sing falsetto. Everybody is different exactly alike! So we’re losing something. That concerns me.

“In the church, that’s not true. People are still sounding individually -- like themselves. If you watch a black church audience, people respond to performer individually. They don’t sit there and applaud as a group. They stand up by themselves and taken on the performers and talk to ‘em. I would that to see us lost that. It is clearly black and it is magnificent!”